So it’s time to make the big move and take your music to the street! Perhaps, you’re going to hit some open mikes or maybe play a few house parties or local pubs with a friend or two. Whatever your plans, you’ll want a pickup for your acoustic guitar. There are literally hundreds of pickups on the market and choosing what’s correct for you could be a daunting task. This article will give you the knowledge to walk into a music store and make an informed decision on your pickup purchase!

Acoustic pick-ups come in three categories, piezoelectric, microphone and magnetic. They are all similar in that they each generate an electrical signal (to be later amplified) that is analogous to the sound of the instrument. They are dissimilar in how they generate the electrical signal. There are different price points on pickup type and the adage “you get what you pay for” certainly comes into play in purchasing a pick-up.

Transducers (Piezoelectric) Pickups

Movement (vibration) of an instrument’s top, back and sides moves the air in the guitar to make the sound that reaches are ears. Transducers utilize piezoelectric technology to generate an electrical signal from the same vibration that moves the air in the instrument and as such, the electrical signal does an excellent job of reproducing the acoustic sound of the guitar.

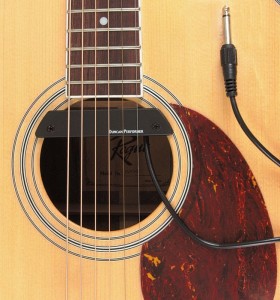

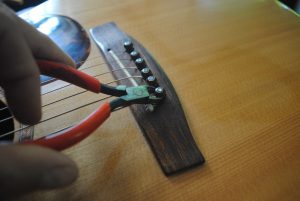

Piezoelectric pickups are usually found in the guitar bridge directly under the saddle (Figure 1) or adhesively attached to the underside of the guitar top (Figure 2). The electrical signals from are weak, and may need a boost in strength via a preamplifier (preamp) that is typically located in the output jack.

Piezoelectric pickups with preamps will have a volume control and possibly a tone control usually mounted on the inner edge of the sound hole. A 9V battery located in the body of the guitar powers the preamp. The preamp draws very little power and the battery will last quite some time before requiring to be replaced. I put about twelve hours of weekly playing on my piezoelectric amplified “work” guitar and change the battery once a year – even then it still has a lot of “juice” left…

Piezoelectric pickups without a preamp are also available. They are less expensive and don’t require a battery. However they lack volume or tone controls and more importantly, your external amplifier may not have the gain to bring the volume up enough to be heard against vocals or other instruments (if you’re in a band). An external preamplifier (complete with volume and tone controls) between the guitar and the amplifier is an option. However, expect to pay around $200 for quality external preamp.

Under-saddle transducers have been reported to “quack” at times – particulary with hard strumming. I’ve only heard this once but have never experienced it directly myself. More on that at the summary of this article.

Microphone Pickups

Just as your ears sense the change in density of the air (sound waves) around them, so does a microphone (“mike”). Located in the guitar body, a microphone generates an electrical signal by senses the sound wave generated by the vibration of the guitar. .

Most are gooseneck mounted inside the sound-hole (Figure 4.) while others are mounted in out-of-sight in the body. The former allows the player to position the mike in various locations around the sound hole. A battery is required to power the microphone. The condenser mike is more power-hungry than a transducer pickup/preamp and thus has a substantially shorter battery life. It’s best to insure your guitar unplugged when not in use and to keep a spare battery in the guitar case. LR Baggs markets a microphone that is permanently mounted inside the body directly under the bridge. There are also a number of less expensive clip on microphones available in the market.

Feedback has always been the boogey man of microphone pickups. There is an asterisk with that statement. Feedback is an issue when in a high amplification environment such as a band that’s really cranking the volume. If you’re playing in lower volume environments such as coffee houses, restaurants, etc., then feedback is a non-issue.

Magnetic Pickups

The movement of the guitar strings in the pickup’s magnetic field(s) generate the electrical signal that is to be amplified. While the body of the guitar plays a role in how the strings vibrate, the sound from a magnetic pick-up is the least likely to accurately reproduce the sound of the instrument. Some magnetic pickup may actually render the sound as a solid body electric!

Located in the guitar’s sound hole (Figure 5), it can be temporarily (with the jack dangling from the sound hole), making it popular with owners of multiple guitars. It can also be permanently installed with the jack in the tail of the guitar. Some have a built-in preamp and are marketed as “Active” magnetic pickups. Actives usually will tweak the tone giving the instrument a more “acoustic” sound.

Hybrid Pickups

Hybrids utilize two pickups -usually a microphone in conjunction with a magnetic or a transducer. A “mix” control determines the amount of signal coming from each pickup – either 50/50 from each pickup to %100 of the pickups. LR Baggs’ hybrids have the microphone permanently mounted in the body of the guitar while most others are mounted on an positionable boom.

A Few Final Words

I regularly perform at coffee houses and restaurants where I use a Fishman “Loudbox Artist” acoustic amplifier for vocals and guitar. My guitar’s pickup is an LR Baggs “Element” active under-saddle transducer. It is also the pickup I recommend for the guitars I build for my customers as I’ve never experienced any “quacking” noise and I regularly receive complements on how good the guitar sounds. As a builder and a performer, this is exactly what I want to hear! I’ve also used a mike/magnetic hybrid and a mike/transducer hybrid. The former didn’t give an accurate sound of the instrument and the latter was twice the cost of the under-saddle pickup with very little improvement in sound. However, the solution that works for me may not work for you! Table 1 below lists some pros and cons of each solution.

| Type | Pros | Cons | Installation |

| Transducer |

|

|

Professional |

| Microphone |

|

|

Professional |

| Magnetic |

|

|

Self |

Table 1

Whatever you choose (or have already chosen), it be great to hear about your experience!

Steve Beckwith has handcrafted over one hundred acoustic stringed instruments to address the need of musicians unable to find the exact sound from mass manufacturing instruments.

Steve Beckwith has handcrafted over one hundred acoustic stringed instruments to address the need of musicians unable to find the exact sound from mass manufacturing instruments.